How to build a strong management team

An Organisational Psychologist’s roadmap to building sturdy and sustainable leadership

The Growth Lending approach to investing is very people-orientated, which means we place significant emphasis on understanding the capabilities of a business’ management team. While reviewing CVs is an essential first step, we go beyond credentials to examine the team’s structure, dynamics, and performance.

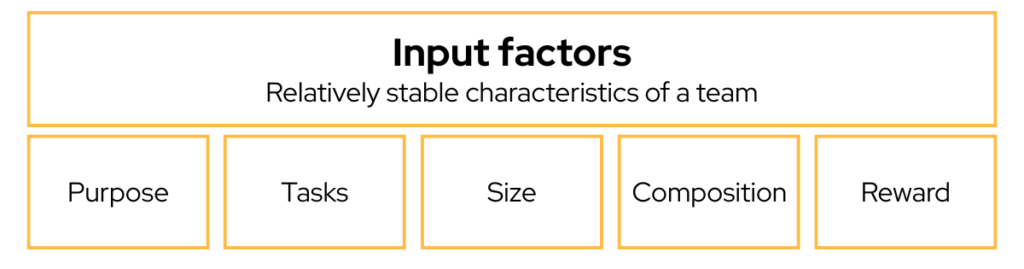

A management team can be assessed across several dimensions, which we will explore in greater depth in this article:

- Who they are and how they are structured (input factors)

- What they do and how they navigate their roles as leaders (process factors)

- How they interact with each other (emergent states)

- What they achieve (output factors)

Surprisingly, the ultimate goal of a strong management team is not perfect harmony. While moments of seamless collaboration exist, the reality for most SME leadership teams is constant adaptation to challenges. Effective teams are built for resilience – designed to withstand setbacks, recalibrate strategies and maintain cohesion under pressure.

1. Input factors: Who is in your management team and how is it structured?

A high-performing management team rests on several fundamental pillars:

- Shared purpose: Understanding, revising, and stating the shared purpose of a management team is essential

- Delineated tasks: Clearly defined responsibilities ensure both joint and individual accountability

- Optimal team size: Management teams should be appropriately sized for their organisation

- Composition: All business areas should have C-level representation, even if leaders wear multiple hats

- Fair and structured rewards: Salary and equity structures should reflect accountability

Purpose and tasks

It may seem obvious, but a management team needs to maintain a consistent shared purpose that sits separate from the organisation’s strategy. Purposes can include maximising the profits of the group, establishing the firm as a training entity, maintaining a particular culture in the business, or perhaps just ensuring the smooth operations of the group. It isn’t the same as the goal for the business – it is a set of aims for the management team itself.

For teams that have never been tried by tough times, it may seem unbelievable that the shared purpose might ever need stating. It seems totally and entirely unnecessary, as organisational goals suffice. However, pressures can put shared purposes sorely to the test and knock a senior team out of shape.

A common shared purpose in management teams of growing businesses is “transparency” or similar, not least because this openness is increasingly something that employees believe they want. But when the news isn’t so positive, it removes a great deal of pressure from a management team if they review the notion of transparency and agree between themselves what ongoing transparency will actually look like. Without resolving this adjustment, some members might be inclined to over-communicate, while others naturally shut up like clams. Far before they decide what and when they are going to communicate, they need to redefine what “transparency” looks like across the management team.

Tasks flow from purpose and, ideally, should not be shared across multiple team members too often. Purpose should be shared, but tasks should go to the right person for each job. Under the banner of shared purpose, a great management team divides tasks clearly, aligning responsibilities with each member’s expertise, experience, and natural strengths. There is a healthy equilibrium between individual contributions, and shared responsibilities.

Size and composition

The size and composition of management teams in small, growing businesses is a topic worthy of extensive discussion. At its core, the critical question remains: does the team have the right people to support the identification and resolution of issues? Do they collectively have the knowledge required to spot issues, work through them and deliver solutions? Does every team member have C-suite coverage? Can the management team make decisions effectively?

In certain situations, a management team can be quite large in relation to the organisation’s size, especially when it has grown organically. While this is a great achievement, it introduces challenges. Team members will often juggle operational duties alongside leadership responsibilities, which can cause tension. Each member must understand whether they are wearing their departmental head or leadership team hat at any given time.

Jeff Bezos’ “two pizza” rule suggests that leadership teams should be small enough to be fed with two pizzas. This principle holds when leaders focus solely on strategy, but in SMEs, where leaders also have operational responsibilities, flexibility is required.

Conversely, some CEOs hold onto decision-making too long, reluctant to delegate due to time constraints or a belief that they are best-suited to make key decisions. While this instinct may have served them well initially, failing to expand the leadership team when necessary creates bottlenecks. A CEO and at least one other senior leader – often a COO or CFO – should form the foundation of the management team.

Reward

In SMEs, remuneration consists of salary and equity ownership. While salary fairness is critical, the bigger issue in accountability is equity distribution. A CEO who retains full ownership shoulders disproportionate responsibility, potentially leading to stress and decision fatigue. While equity does not need to be distributed equally, shared ownership fosters a stronger sense of collective accountability.

Final thoughts

There are some non-negotiables in a high performing management team. It is very hard to argue against a need for shared purpose and delineated tasks. After that, there are genuine choices to make, but team size, composition and reward structures need to match the way in which the CEO wants the management team to operate.

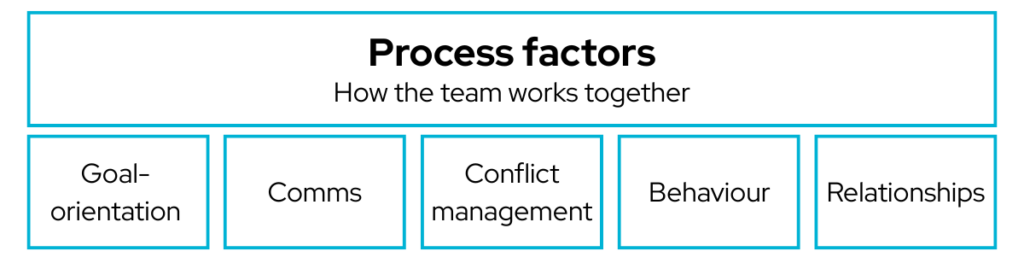

2. Process factors: What does your management team do and how do they navigate their roles as leaders?

- Conflict management and goal orientation: These are placed together, as any management team needs one to achieve the other

- Communication: Comms are often the bugbear of senior teams, but it is suggested that checking understanding is even more important than getting the messaging exactly right in the first instance

- Behaviour and relationships: If a management team gets this right, and behave collectively in a way that they each find helpful, they will automatically influence the rest of their organisation positively.

Conflict management and goal orientation

I have reordered these elements and put these two together. That’s because they are practically impossible to separate – if one is ineffective, the other inevitably suffers. Communication becomes much easier if these two elements are in working order, so that comes next.

Conflict management suggests that a management team is able to resolve conflict when it occurs. I’m going to put it far more strongly; managed conflict is a vital element of any high performing management team. It is a key tool of success.

Inexperienced management teams mistake the need to show a united front as a requirement to consistently see eye to eye. In reality, it’s far more productive to have a leadership team that debates and even clashes over decisions, as long as they have the shared respect to resolve these disputes properly. Debate and resolution are essential to consistently making the best decisions, as is an attitude of “you win a few, you lose a few” in each member of the team. Otherwise an organisation can eventually sink under the weight of “good enough”s or, even worse, “anything for a quiet life” acquiescence.

Getting this right should not take a huge effort, purely because of the traditional roles of the two most common founder members of the management team. The CEO is pushing forwards, sweeping everything along in their wake, while the COO or CFO (depending on the type of business) comes behind with their proverbial dustpan and brush. You’re already looking at a healthy natural contrast. The danger point is when the team expands and the roles become mutable.

While these debates can be about anything, they need mostly to be about the goals of the business. Debate shows that the people involved care enough about the future direction of the business. They show that people have thought deeply about what they want the business to achieve. A proper debate, with each person giving their unique perspectives, enables a management team to really reach around the corners.

A CEO is likely looking at future opportunities, the CFO is perhaps focusing on what has been successful in the past, the COO is thinking not just about what the team can do now, but what they will be able to do. Whether the debate is between two, four, or more people, the business goals are more likely to be SMART if everyone has had their say and thrashed out the options. And then, having gone through that process and looked at the details in depth, the team is going to be more closely-aligned to both overall goals and short-term focus.

Communication

Communication is too frequently seen as an end- or by-product of management team activities, but getting this right is absolutely core to every successful team. Strong communication is a driver, a check, a balance, a motivation tool, a solace, a connection with the overall team.

A management team that appears to function well but communicates poorly will ultimately struggle when tested. A management team that seemingly functions well, but communicates poorly will, when put to the test, also be seen to fail to function well. If this sounds extremely circular, that’s because everything here is interconnected.

There are many ways to communicate and many different messages to share, but when this is boiled down to essentials, a management team that doesn’t communicate effectively allows a space to grow in their organisation for gossip and conjecture. As gossip and conjecture grow, there is an initially imperceptible effect on the engagement of the team. This can be recognised on a practical level – a team that gossips isn’t doing any work while engaged in that particular activity – but then it becomes more of a mindset shift and it is discretionary effort that diminishes. The end game of this transition is a “them and us” mentality, at which point the management team has fewer levers to pull to whip the team into action. This grows purely from a few missed opportunities to speak to the team.

The best way to encourage healthy conflict in well-mannered teams is to put potentially contentious items on the agenda purposefully and invite submissions of key points ahead of time. Sharing these in advance ensures everyone has a voice and enables structured discussion. With this approach, consensus is reached more systematically, and an acceptance of “you win a few, you lose a few” for each individual member becomes second nature. Momentum builds. Just occasionally, the older ways of doing things (i.e. creating agendas and inviting submissions) has more merit than the new and ad hoc disagreements are rarely productive.

Putting this all back together, management teams that function best do debate, do disagree, but then create far greater internal alignment. This then enables them to communicate more confidently and reliably and the links with their team are maintained.

Behaviour and relationships

A management team’s behaviour inevitably shapes the wider organisation. Managed conflict is a great example of behaviour most management teams would want to see in their organisation, but there are others. Decision-making is another critical behaviour that should be modelled across the organisation.

If leaders avoid difficult decisions, so will their teams. If they allow discussions to become personal, their teams will mirror that behaviour. If they have side discussions, so will the team. The aim is not moral perfection – no one benefits from self-righteous leadership – but rather for the right checks and balances to set the tone for the organisation.

Similarly, the strength of relationship and attendant behaviours between the members of the management team should match what you want to see in the team.

Final thoughts

This approach fosters not only optimal problem-solving and alignment, but also a culture that reflects these positive behaviours at every level of the organisation. This helpful, positive behaviour will flow down into your organisation and result in you seeing many more of the behaviours you want to see. Most importantly, this alignment makes effective communication significantly easier, a topic explored in the next section.

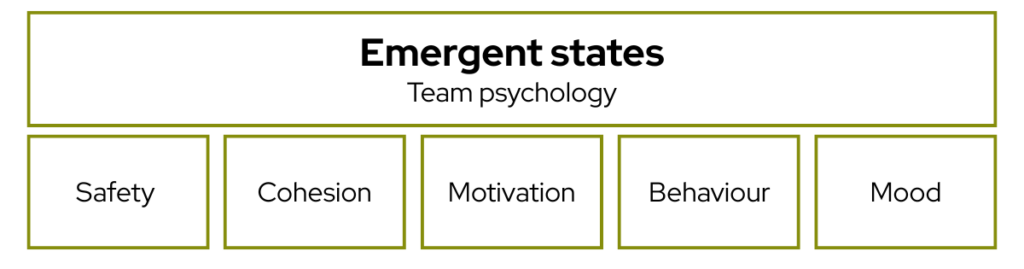

3. Emergent states: How does your management team interact with each other?

Emergent states simply refer to the different attitudes and feelings that develop within the management team over time. They form when the team forms and become more and more consistent over time. This captures how their shared beliefs (about their organisation, teams, clients, the economy etc) crystallise and affect their motivations, feelings and moods.

- Safety: This relates specifically to psychological safety. It is far more than a nice-to-have in a well-functioning management team

- Cohesion: This can seem to act in opposition to conflict management, but it is just another aspect of how a senior team works together

- Motivation, behaviour and mood: These are aspects of team psychology that need to be nurtured within a management team

Safety

The type of safety at stake here is psychological safety. This describes a shared belief that individuals can speak up, express ideas, ask questions and admit mistakes without fear of embarrassment, punishment, or other negative consequences. It fosters open communication, trust and innovation by ensuring that team members feel respected and valued, regardless of their level of contribution or challenges.

This can seem very idealistic to many leaders. They themselves may never have experienced needing this safety, or perhaps they did, but they didn’t get it and pushed through anyway. To some, there is a sense of indulgence surrounding the entire idea. However, as with so many of these concepts, it is important to stress-test this notion in the toughest times.

When something significant and challenging happens at work, is it better to have team members who are so anxious that they are unable to think straight? Or is it preferable to ensure that, although they may realise the gravity of the situation, they are able to remain in full command of their faculties and think clearly? If a management team wants to preserve the best problem-solving capabilities in their team when the pressure is high, psychological safety is essential. Without it, those capabilities will erode.

The first step to achieving psychological safety is counterintuitive – a management team needs to know how they will constructively manage poor performance. A structured process provides a safety net. When a management team understands that they can address performance issues constructively, they have a backstop – they know that if positive efforts fail, there is a clear course of action. It is much harder to avoid.

In organisations where psychological safety is maintained, management teams can influence behaviours positively, manage performance constructively and successfully push and pull the levers necessary to achieve their goals. They can look across their organisation with clarity and appreciate the many ways in which their team is working together.

The loss of psychological safety has happened repeatedly in more organisations than not. Even though these teams may not be inherently harsh, they can find themselves in an invidious pattern of blame. If this has already happened in an organisation, then multiple fixes are required. However, if this is still at the stage of avoidance, there are some key ways to remain vigilant.

- Check understanding: Communicating clearly and unambiguously is not a skill automatically bestowed upon those who end up running businesses. It isn’t something that happens effortlessly. Effective communication is something all senior people should aim for, but in the meantime, they need to check that their messages have been understood. If messages are unclear, multiple interpretations will proliferate and psychological safety will be easily threatened by mixed messages.

- Avoid blame: There is a distinction between holding people accountable for delivery, quality and performance and blaming them for failure. The first is part of the employer-employee contract, while the second has no place in any workplace. Linguistically, “Colin’s project is over budget and running out of time” presents a problem to diagnose and fix. “The failure of this project is all down to Colin” may or may not be correct, but at least leaves room for investigation. “Colin is lazy and never shows his face” is simply gossip. If management teams believe they can speak this way behind closed doors without the organisation noticing, they are mistaken. Blame seeps downward, and a failure to address the real issues can have imperceptible but devastating knock-on effects.

- Steer clear of punishment: Borrowing from transactional analysis, punishment is always dispensed from the Parent position. As soon as a management team starts thinking in terms of punishment, they have occupied the Parent position and forced their organisation into the Child role. Some organisations even refer to their staff as “the children.” When this happens, employees exhibit a range of unhelpful behaviours, from blatant defiance and disengagement to fearful compliance. Defiant employees withdraw discretionary effort, while compliant ones lose confidence and require approval at every step. No healthy organisation can function effectively under these conditions. Workplaces are composed of adults and leadership must treat them as such.

Apart from requiring self-awareness from the management team, there is no downside to protecting psychological safety. However, allowing its deterioration has severe consequences.

Cohesion, motivation, behaviour and mood

A management team should be bound by the same glue that holds the entire organisation together. The affable, well-liked management teams mentioned earlier often intuitively understand this. They naturally model the moods and behaviours they want to see in their teams and they see their motivation and energy reflected positively in the organisation. However, this approach does not always hold up under pressure. When challenges arise, management teams may become frustrated if they feel their positive behaviours are not mirrored by employees. This frustration can, in turn, lead to internal fragmentation and irritation among team members.

Rather than allowing frustration to build, a management team should double down on supporting each other. Taking care of each other’s motivation levels and well-being ensures the team remains cohesive. In difficult times, businesses need many things, but above all, they require a well-functioning management team. A senior team must prioritise supporting one another because, ultimately, this is the behaviour they need to model for the rest of the organisation.

Final thoughts

It is remarkable how effectively culture, behaviour, and mood flow down from the top. Any management team can and should think of themselves as a microcosm of their organisation. Once they have determined how they will behave among themselves, the next step is simply to be visible and lead by example.

4. Output factors: What does your management team achieve?

Finally, we get to what you have to show for all this effort – the achievements of a management team’s organisation. Management teams hold themselves to account, so they need to measure their own performance.

- Task and project performance: Most smaller organisations see no clear delineation between tasks and projects, but whether there is separation or not, this performance needs to be measured

- Wellbeing: It is important to note that this is framed here as a management team output and not something that runs alongside the work itself. It gets equal billing with the work achieved

- Growth: I have encountered incredibly successful organisations where standing still is the output they desire, but in most organisations, growth is the ambition so also needs to be measured and appraised.

Task and project performance

In some organisations, it is clear where day-to-day operations end and special projects begin. However, in smaller organisations, these often blend together. A distinction is useful when an organisation leans too heavily on one type of work over the other. If the team excels at special projects but struggles with routine tasks, or vice versa, separating the two can help balance priorities.

Regardless of structure, management teams should collectively own the organisation’s successes. A CFO or CHRO must share in business development wins, just as a COO should celebrate marketing achievements. A truly cohesive team naturally embraces shared success. For home-grown management teams, this may feel unnatural at first, but adopting a collective “we” fosters a stronger, unified leadership approach.

Individual and team wellbeing

A management team that values the wellbeing of its workforce must equally prioritise its own. Leading by example means avoiding burnout, taking time off when needed, and ensuring sustainable workloads. Too often, management teams adopt a “do as I say, not as I do” approach, which causes disconnection, particularly in challenging times.

Hard work, when shared towards a well-defined goal with a realistic chance of success, can be highly engaging. However, sustained periods of excessive work without a clear endpoint lead to disengagement.

Wellbeing is an essential management team output, not a side concern. High-performing organisations balance engagement, attainment, and professional growth. Pressure is not inherently harmful, but chronic stress is. By modelling and promoting wellbeing, management teams create healthier, more effective organisations.

Growth

Growth applies at multiple levels – individual development within the management team, the team’s collective evolution, organisational growth and expansion of customers or brand presence. Evaluating all forms of growth is essential, but need not be overwhelming if approached systematically. When a management team evaluates the team, they can evaluate themselves, even including 360 feedback if that suits their culture.

Without periodic reflection, teams risk becoming bogged down in their daily tasks, failing to recognise progress and missing out on opportunities for improvement. Regular assessment of growth can power sustained momentum and continued success. Even when times are tough, it is a rare management team that has nothing to recognise or even celebrate. When an individual passes through the portal of senior management, it is a sad thing indeed if their professional development stops there. But a collective assessment of progress adds more than growth; it is actually team building. Done carefully and fairly, this is a perfect opportunity to increase inter-team trust.

Final thoughts

Effort without recognition leads to diminished motivation, while failing to evaluate activities results in repeated mistakes. Assuming that senior leaders instinctively gauge their performance is flawed – some are overly self-critical, while others never self-assess. Neither extreme is productive.

A management team dedicated to excellence must regularly ask, “How are we doing?” Even in difficult periods, there are successes to acknowledge. Taking time to reflect benefits individuals, the senior team, and the entire organisation.

As you can see from above, building a strong management team is about more than simply clubbing together individuals with the right skills and knowledge. Building a team that is effective, sustainable and that can genuinely drive business outcomes must be very intentional and while not exhaustive, following the roadmap I have outlined in this article is a great place to start.

- Want more information on developing leadership in a fast-growing SME? Contact Heather here